"I wish I had been

born before the Civil War and had died at

Let’s End the Civil War!

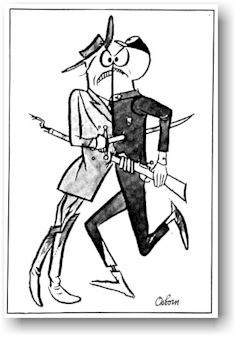

Re-fighting yesterday’s

battles will never solve today’s problems.

By Harry Golden

(Saturday Evening Post, 11 August 1962)

There

were more Confederate flags sold during the first year of the Civil War

Centennial (1961) than were sold throughout the South during the war itself

(1861-1865). One hesitates to estimate the number of Confederate flags that

will be sold during the next three years, but the prospects are that the total

will be more than all the flags sold in all the wars the nation has fought.

Yet

the Civil War Centennial is hardly a promotion dreamed up by flag manufacturers.

Nor is the centennial merely a project of the enthusiastic city booster to lure

the tourist dollar. No city booster anywhere in the South or in the North has

any intention of proposing a celebration of World War I or World War II or the

Korean War.

We

celebrate no other war because essentially we believe those wars are over,

their outcomes final, the course of history decided. But there are centennial

committees throughout the South which would have us think the Civil War is not

done with, that it ought to be refought. These fellows grow beards, wave flags

and charge over the few meadows the housing developers have left—hoping somehow

by this exertion to sustain the illusion that the South may yet snatch victory

from defeat. They do everything to re-create the Old South except save

Confederate money.

The

war started again in July 1961 with the grand reenactment of the Battle of

First Manassas (

The

son of a friend of mine, a "corporal" in the Guilford Greys

(Greensboro, North Carolina), has been "killed" three times since

First Manassas and is perfectly willing to give his life in a fourth reenacted

battle. It is nice, indeed, to have more than one life to give to one's

country, although the plane fare to the different battlefields is considerable.

The

centennial engenders nothing if not sacrifice. The late Bill Polk, editor of

the Greensboro Daily News, once

showed me a letter from a

These

mock recruits, I suspect, secretly hope one day the batteries will load real

projectiles in the cannons, and the bayonets will be cold steel, not rubber.

And this time they will take

On to

Once

they take the capital, they can force upon the Supreme Court the decisions that

will restore the old plantations, the crinolines, the dueling pistols, the

house on the hill with smoke coming out the chimney at twilight and little

Sambo rolling in laughter under the magnolia. Ah, what a dream!

Yet it is not entirely an idle dream. The Civil

War centennialists have some vague idea that, if they can mount a sufficient

show of force, they may not have to deal with the more aggravating and

immediate problems of Southern life - the problems that press upon an urban,

industrial area that is leaving behind the old, easy agrarian values.

Yet it is not entirely an idle dream. The Civil

War centennialists have some vague idea that, if they can mount a sufficient

show of force, they may not have to deal with the more aggravating and

immediate problems of Southern life - the problems that press upon an urban,

industrial area that is leaving behind the old, easy agrarian values.

Thus

the centennial has turned into a party rather than a pageant. I have even seen

a few automobiles decorated with the Stars and Bars, filled with Negro

students, each of the occupants therein wearing the butternut-gray dinks of

Confederate soldiers. The centennial is democratic, and that may be its

weakness. No centennial committeeman, no matter how skillfully he ties his

bowstring, is completely unaware of what is going on in the business district

of his hometown. He doesn't even have to work behind a store counter to know

that, in the states of the old Confederacy, at least one third of all the

purchasing power and one half of all the credit buying comes from the pockets

of grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the Negro slaves.

That

realization is why the centennial is something less than a huge success in the

big Southern cities. The plan for my own home,

Such

lack of interest is reflected in the local press. During the past year the

papers carried only two short wire-service items. One from

Outposts in the

Twentieth Century

Thus,

the serious centennial committee pretends the war took place among other

peoples in other times. The committeemen would have it that it was a gentleman's

war. As Carl Sandburg says, it thinks of the Civil War as it thinks of Sir

Walter Scott's Ivanhoe.

The fact is, however, that the Civil War was the first modern war. It was the war the North won because the North realized it was an industrial war - a war won by a superior advantage in men, materiel, transportation and logistics. All wars since then have been won in this way, which is why the North finds it harder to throw itself unreservedly into the centennial celebration. The Civil War was a continuation of the North's history, not its climax, and it is far more difficult to verbalize and mythologize about continuity. Thus the celebration in the North has been largely carried on by publishing ventures.

Books on every conceivable aspect of the war inundate library shelves. But then, the North has always been, according to many Southerners, materialistic. Whether the centennial celebration has brought the publishers profits, I have no way of knowing. While it is eventful to read books by Bruce Catton and Lenoir Chambers, I am not sure I can devote the time to obscure major generals and books based on such ideas as "I Rode With Longstreet," "I Rode With Lee" and "I Rode With Jackson.”

In

1962 the North does not need instruction. It knew in 1862 that it was fighting

to preserve the

For any reader not yet persuaded of the silliness of the centennial, I recommend Catechism on the History of the Confederate States of America. That little brochure, issued by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Tennessee Division, and intended for the patriotic instruction of the Southern child, has such questions and answers as:

Q: Did slavery exist among other civilized nations?

A: Yes, in nearly all.

Q:

Why did not slavery continue to exist in the State(s) of

A: Because they found it unprofitable, and they sold their slaves to the States of the South.

Q: How were slaves treated?

A: With great kindness and care in most cases, a cruel master being rare.

Q: What was the feeling of slaves toward their masters?

A: They were faithful and devoted and were always willing to serve them.

But if you really want an exhibition of plunging fully clothed into the past, think of one of the centennial committees, whose members pledge themselves to talk up John C. Calhoun at cocktail parties, ball games and backyard barbecues. John C. Calhoun was one of the tragic figures of American history. He so badly wanted to be President that he managed to author a lot of the South's woes by insisting it save its liberties by maintaining slavery and a plantation economy. I don't care how well prepared the barbecue is, it is not easy to digest John C. Calhoun as the long-lost Southern prophet.

I

doubt, however, that any committee would ever propose a dramatic pageant to

herald the day James B. Duke, the tobacco tycoon of

And since Buck Duke's time, every mayor of every Southern

city, every chamber-of-commerce secretary, every state legislator, has been

scurrying through the North looking for industry. In the past thirty years they

have found it, too. Parts of

The ideas which the mayor, the chamber-of-commerce

secretary and the legislator sell the Northern manager arc not the ideas of

chivalry and honor and family. They are instead the ideas of the middle class,

the ideas of city people who run factories, sell cars and manage national

distributorships. Certainly they are not the values of an isolated, provincial,

agrarian aristocracy. They are the values of the people who have had and

continue to have the comfort and prosperity of the industrial middle class of

Was the "Old

South" a Myth?

The

chamber-of-commerce fellows are selling the ideals of the modern industrial

world because the ideals of the Old South were only make-believe currency. The

Old South nourished because Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, and the cotton

gin followed appreciably after Dan’l Boone hiked into

The

fact is that the Old South was nothing more than a myth and a poem and as

The Civil War started with the Negro in slave cabins. But all of the blanks and muskets and beards and chattering Calhoun champions will not disguise the truth that Negroes serve today on the Republican and Democratic national committees. The real Confederates found cover behind occasional tar-paper shacks. In their place today, the recreated regiments and brigades have to charge around factories where the skilled workmen inside knock off a few minutes to cheer them on.

The

time has come to end the Civil War because we are one country with one economy.

We cannot take time out from industrial and urban problems of unemployment,

housing, schooling and civil rights to indulge ourselves in silly excess,

celebrating a time that no longer is - and never was. The truth is that, at

best, the rather expensive centennial provides but a minor amusement for the

people who are paying off mortgages and putting by the money to send a son to

the

THE END

Harry Golden is the

widely quoted (New Yorker transplanted to North Carolina) editor of The Carolina Israelite and author of

several books, including the best seller Only

in America, For 2c Plain, and the newly published You’re Entitle'.