The

Shock of Authenticity and Dorfy Hatts

In my readings about the American Civil War I have come across the phrase the American Iliad so often I finally decided to find out for myself exactly what this meant.

I began with an Internet search, where I learned that not

only is the phrase the title of a book about the Civil War by Charles P. Roland, but that somebody had used it in conjunction

with Richard M. Nixon! (Given that the Iliad deals with a long war

involving massed armies, it is clear to me that the Civil War association is

more valid than the one with Nixon.)

I decided to get to the heart of the situation and read Homer s Iliad. I must confess to having been of two minds about the prospect. On one hand I was familiar with some of the stories and incidents due to a lifelong interest in art, and was looking forward to reading the original source account. (For instance, who was Cassandra and why would somebody want to rape her?) On the other hand I have never liked poetic storytelling. Being interested in Arthurian literature, I waded into Alfred Lord Tennyson s Idylls of the King at age fifteen and developed a distaste for metered prose. So I knew Homer would be difficult for me. And he was.

Without going into the details of the Iliad, suffice to say that this effort led me into an interest in Homeric Greece, which led me to renting some Greek films derived from classical tragedy, which led me to the first matter I would like to discuss: the 1956 Robert Wise film Helen of Troy.

It is awful. I m the sort of chap, however, who needs to analyze just why a film is awful and not be content to simply call it that. The fault behind this one was readily apparent: it was far, far more reminiscent of Hollywood in the 1950s than Greece and Troy in the late Bronze Age. My rented tape had a truly terrible Warner Brothers filmed promo about the dedicated research and detail that went into the film. (Does this sound familiar? It should. Hollywood publicists make the same kind of noises about all period films including, of course, Civil War films no matter how farby they turn out.) It didn t help that the fellow extolling the virtues of Helen of Troy talked about the duplication of Renaissance palaces, and mentioned the Roman god Neptune. (In the Iliad, Homer frequently calls Poseidon Earthshaker. )

Just about everyone in this film had straight white teeth. Helen s slave girl (Brigitte Bardot) had the full Max Factor treatment, as did Helen which admittedly makes more sense for Helen since she was a queen. Short poodle cuts were all the rage in the Fifties, and Helen sported one herself with a fall as a nod to authenticity. Paris was clean-shaven and could have just as easily been a mid-Fifties American baseball hero. Worst of all, the emotions, motivations and actions of everyone in the film were readily understandable. Why is this so wrong? Obviously, if the audience wasn t comfortable with the production, Warner Brothers wasn t going to sell any tickets, right?

Let s look at another film set in the Heroic Age, the 1962 Michael Cacoyannis film Elektra, starring the awesome Irene Papas in the title role. The film is adapted faithfully from the play by Euripides. This is one of the great filmed expositions of the femme fatale but not only that, it seems authentically ancient in feel. True, the acting styles in this film are more natural and better suited to a modern audience than the way the play would have been acted for a contemporary Greek audience. Some of the authenticity in this film comes from one odd sequence when Elektra meets her brother Orestis after they were separated as children. Orestis plays a sort of identity game with his sister that is puzzling to modern moviegoers I certainly found it so. Why does he do this? It seems jarring, given the circumstances. I have read criticism of the play that gives the answer the sequence met the needs of ancient Greeks for psychological drama.

All of which leads me to a conclusion: if you are perfectly comfortable watching a teleplay or movie set in some time other than our own, you understand it perfectly and nothing in it jars or shocks you, I suspect you are watching something that is not as authentic as it should or could be. You are probably being coddled and patronized by Hollywood.

The Shock of Authenticity

What I call the Shock of Authenticity is that jolt a little bit of dialog, theme, costuming or make-up that tells you that you aren t in Kansas anymore. It gives an undeniable feel to a film that cannot be gained by publicists insistence that massive amounts of studio research was conducted in an effort to gain authenticity. It can come in the oddest, most unexpected places. Some examples:

- In the 1991 British television production of the 1747 Samuel Richardson novel Clarissa, there is one scene set in a London brothel. One of the prostitutes walks up to one of the male characters, smiles - and reveals a set of yellowed, rotting teeth. Yikes.

- The 1978 Eric Rohmer adaptation of the Arthurian romance "Perceval le Gaullois" has period background music and chants by a sort of medieval chorus that seems very odd to modern ears. The script is very faithful to the Medieval source romance by Chr tien de Troyes, so the themes, action and narrative, while they may have made sense to period readers, seems rather bizarre to us. A stong level of religious belief on the part of the reader (or viewer, in this case) is assumed, and the movie concludes with the Passion of Christ!

- The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, with origins nearly 5,000 years old, is the oldest surviving epic in the history of mankind. Gilgamesh's great friend is named Enkidu. It is pronounced "inky-doo." A downright odd name for an epic character.

- In Ridley Scott s excellent film The Duellists, Harvey Keitel portrays a French solider in Napoleon s army. After cutting his dueling opponent in the face with his saber, he cries, La! La?

- In another wonderful Irene Papas film derived from ancient Greece, Antigone, the entire action of the story (and multiple deaths) is driven by a sister s desire to properly bury her brother s body. This is not a motivation instantly recognizable to an audience today.

The shock of authenticity is not confined to movies. It can also be experienced in an authentic place.

- Stepping into the rooms of George Washington s Mount Vernon for the first time, I was stunned to discover that the Founding Fathers taste for wall paint extended to lurid, heavily-pigmented hues of electric blue, dark mustard and emerald. It didn t look anything like modern decorators pastel interpretations of 18th century American style.

- In a museum in Berlin, Germany, I stumbled upon a marble bust of Cleopatra of Egypt described as being taken from life. I never really expected Liz Taylor and early 1960s eye shadow, but a subtle beauty combined with a prominent nose was a surprise.

- While Tom Sawyer has a point in claiming that There ain't anything as interesting as a place a book has talked about, I recall being distinctly unimpressed with Burnside s Bridge on the Antietam battlefield when I first visited it.

That little suggestion of a bygone time or place doesn t require THX sound, a lavish orchestral soundtrack or Cinerama. It just takes the right hint or nuance, delivered by somebody who has a feel for the period being represented.

Dorfy hatts

To my mind there were only two good things about the film Helen of Troy. One was subtle, one was not. The subtle one was seen very briefly during the battle between Achilles and Hector it was the Greeks standing on the sidelines watching the battle and rattling their spears. The effect suggested something I once read described in a Civil War journal, that of the sight of the high bayonets (muskets carried at the right shoulder shift) of the Army of the Potomac winding its way up the South Mountain passes on the way to Antietam. The writer described the flashes of sunlight on the bayonets looking like a great metallic snake.

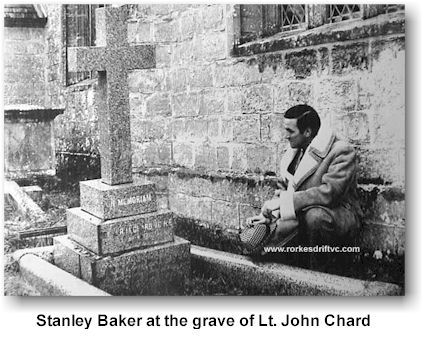

The good unsubtle thing about Helen of Troy was Stanley Baker, who played the Greek hero Achilles. (You will remember this actor as Lt. John Chard in the reenactor favorite Zulu.) As Achilles, Baker s testicles could almost be heard clanking together as he walked to mount his chariot. Wearing a trimmed, pointy beard of the type seen on Greek vases, with the staring eyes of a frenzied Klingon and impetuous manner, Baker seemed every inch the Homeric hero. What really put him over the top, however, was his dorfy hatt.

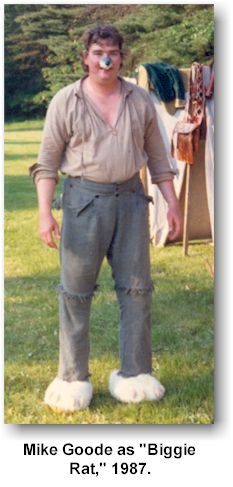

But first, a definition of terms: my New Jersey reenacting pard Mike Goode (to whom I once gave the name Miles B. Marching in an article we wrote together) invented this term. Describing the martial high he got while doing a Revolutionary War light infantry impression, Goode said that one of the things that helped him assume the role of a berserker was his dorfy hat. (I doubled the t in the phrase to make it look more colonial.) The fact is that his and I have to call it this - Homeric physique (which I also have) made him more the tall and solid British grenadier type than the nimble light infantry type mattered not. That dorfy hatt liberated his soul.

So it was with the alpha male Achilles. I had always wondered what the design thinking was behind those crazy Greek helmets with the brushes and horses tails on the top. In the Iliad, Homer explains that the shaking and quivering brushes and horses tails looked terrifying in battle. (At one pointing the Iliad, Hector s helmet frightens his small child as he bids his wife and child farewell to go into battle.) Separated 3,200 years from the Grecian Bronze Age, we shall have to take Homer s word for it. But, if you think about it, down through history there has been an odd affinity between dorfy hatts and a militant attitude that must be a deep characteristic of male nature.

- Apparently not having dorfy hatt material, ancient Gauls worked lime into their hair to produce whitened spikes.

- Revolutionary War soldiers wore hats with points cocked hats. I can tell you from firsthand experience that keeping one s musket barrel from catching a point and knocking the hat off one s head while marching at shoulder arms is no mean feat.

- Imperial Prussians wore helmets with spear points on the top, suggesting that they d like to ram into their enemies head first.

- 18th century British Grenadiers wore heavy bearskin hats that gave them the overall appearance of a dirty Q-Tip.

- Civil War Federal troops wore forage caps with flopping tops that suggested woolen material was over-abundant in the North. Could it be that floppy forage caps were intended to terrify opposition troops in the style of horsehair? Nawww, they look way too comical.

- A 12th century knight in Anjou, France frequently stuck a little yellow flower native to the area, the planta genesta, in his helmet. His family and dynasty, the Plantagenets, came to be called after the helmet decoration. We have all seen Civil War reenactors stick various bits of flowers, springs and flora in their hats in the style of Geoffrey of Anjou.

- A rugby player takes a certain kind of pride in wearing a scrumcap, and they can look dorfy (my wife claims mine looks like a diaper worn on my head). Some rugby forwards wear a band of electrical tape wound around the ears. The reason is the same: to keep the ears from being torn off in scrums.

It is with rugby, and, specifically, Maoris, that I think I have the male psychology behind the dorfy hatt. The New Zealand national rugby side, the All-Blacks (named after their black team clothing and not due to racial makeup) perform what is called a "haka," or war-cry, before matches. The British settlers in New Zealand got it from the Maoris. A weird chant is shouted, eyes bulge, veins on necks stand out, hands quiver and tongues are extended. I think I know what s intended to go though the minds of the opposition players watching the haka being performed: My God, what on earth are those people doing? They look absolutely crazy. So I believe it is with the dorfy hatt: My God, look at those ridiculous hats! What sort of moron would wear something like that? Walking around in society wearing something like that is just spoiling for a fight.

The media have been trying to identify a male crisis stemming from about the 1970 s. Can it be a coincidence that from then to the present the perfectly usual and unremarkable-looking baseball cap has become the universal headgear in America? The tough guys in films noir all wear fedoras (dorfy name for a hat), not baseball caps. And consider Samson. His strength and vitality was closely associated with his hair. Heaven knows how mighty he d be wearing a scrum cap or a Trojan helmet.

I expect that someday, some genetic scientist will discover that the very same gene that causes extreme behavior in Y-chromosome holders also leads to a desire to wear idiotic headgear. I await vindication for my dorfy hatt theories.

Note: By writing this article I fulfill a promise I made to my pard Mike Goode back in 1987, to explore the thinking behind crazy-looking military hats. Mike passed away a few years ago; just before he did I exchanged e-mail with him and discovered that he played rugby years before I discovered the game. He and I played the same position, Second Row, or Lock. A position suited for the largest men on the team, it s one you might expect a larger-than-life Homeric warrior to play. I hope he is relaxing in some Hall of Heroes, or a suitable rugby pub, reading and enjoying this essay about dorfy hatts.

POSTSCRIPT: I saw a whopper of a farb production the other night, and a textbook case of where the Shock of Authenticity is wholly absent as intended, but all too apparent where not intended. What do I mean? "The Last Days of Pompeii" (1935) was set in an Italian city around the time of Christ. That's one period. However, this production doesn't invoke that era nearly as well as it does the Depression Era in which it was made. Many of the characters - with one notable exception, described below - act like extras in a Warner Brothers gangster film, with "Why I oughtta..." and "Say, that's swell!" period mannerisms. Only they wear Roman helmets rather than snap-brim hats. A little boy looks and acts like one of the Little Rascals. And then there's the matter of the script, which invokes yet a third period: the sentimentality and maudlin religiosity of the Victorian age. Although the opening titles claim otherwise, the script is very reminiscent of one of those terrible historical novels by Edward Bulyer-Lytton. (As a teen I read and enjoyed his "Harold, the Last of the Saxon Kings." When I turned to it again as an older man, I was shocked by how awful it was.)

The one notable performance in this film is Basil Rathbone as Pontius Pilate, who gives a moody, thoughtful and convincingly timeless and undated portrayal. But perhaps I am biased because of an interest in the character. When I was sixteen I read a biography of Pilate, mainly because of the thought-provoking song in the rock opera "Jesus Christ, Superstar," which I had become familiar with the year before. "And then I saw/Thousands of millions/Crying for this man/And then I heard them mentioning my name/And leaving me the blame." Good stuff, that. Elevates Pilate to the level of Greek tragedy.

Mel Gibson is working on a production about Christ's last days that is not only authentically bloody, but spoken entirely in Aramaic and Latin - without subtitles! Unless I am mistaken, this one could be sub-titled "The Shock of Authenticity." I'll be interested in seeing it! - Jonah

ANOTHER POSTSCRIPT: I saw a made-for-cable production the other night about the Trojan War; this one was also entitled Helen of Troy, and starred Rufus Sewell as Agamemnon. It had its faults, but was far better than the 1950's movie of the same name I review above.

Once again, the late Bronze Age Achaians are wearing classical Greek armor. I guess the producers figure the audience wouldn't accept anything else as being anciently Greek. But the really major problem with this movie concerns Sienna Guillory, who portrays Helen. Casting for this part is always a challenge - you have to find an actress with a face that would launch a thousand ships. In other words, Liz Taylor, Ava Gardner or Hedy Lamarr in their prime. Mrs. Begone pointed out what was obvious to me: Guillory just doesn't have that face. (And she has a rather big butt, which seems to be featured in a number of the scenes.) In fact, we both agreed that Sienna Guillory is pretty rednecky-looking. Would any man wage a ten year foreign war for the likes of her? No. Concerning this, the director makes a major goof in a certain scene, when Helen, dressed in a rather flimsy and clinging dress, runs past a couple of men walking down a street. I don't know about you, but if a woman wearing a flimsy and clinging dress possessing a face that could launch a vast number of naval vessels ran by me, I'd turn around to look as she went by. Not these two.

Also, Achilles looked like a World Wrestling Federation dork. Unforgivable.

Anyway, it was better than the 1950's movie, but far short of what it could have been. We'll see what 2004 gives us with "Troy."

YET ANOTHER POSTSCRIPT: I finally saw "Troy." I am now convinced that an adaptation that is faithful to the Illiad will never be produced. Audiences won't accept gods who involve themselves in the battles and act like spoiled children, and the overall general level of foreignness that is Homer's work. Perhaps it's just as well. The Illiad needs to be read in order to really be appreciated. While Troy was entertaining, I now judge filmed adaptations by how likely they are to compel audiences to seek out the source works...

For those of you interested in the matter of the Trojan War, I can recommend only one work: Michael Wood's 1985 documentary "In Search of the Trojan War," which is captivating. Everything else is Hollywood.