He Was There

By Jean Mitchell Boyd

(in Mysterious New England printed by Yankee

Magazine)

The rain danced on the roof and its silver

fingers tapped on the windows. The wind haunted the comers of the house and

seemed to cry to come in-to come into the library of Mr. Gideon Welles,

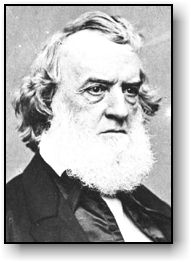

Secretary of the Navy during the Civil War. The "Old Man of the Sea"

he was sometimes called. We sat there in the library on that rainy afternoon,

Mr. Welles' grandson and I. It was a wonderful place for children to read. The

library was not on the first floor. Opposite the front door was a broad

stairway with a polished banister. It was the best banister on the street for

"sliding down." The stair carpet was thick, so that as you climbed to

the landing it was like walking on oysters. If you were going to the second

floor, you turned to the right and climbed more stairs, but the library was one

high step from the landing. It may have been an ell, added after the old brick

house was built. The roof was flat and made a nice dancing floor for the rain.

There were windows on three sides, making the light good for reading. The bookcases

went up to the ceiling. Many of the books were bound in canvas and were worn as

if someone loved them and read them.

Mr. Welles

had come to Hartford in 1869, after he finished his second term as Secretary

of the Navy. He lived there until he died in 1878. Those of us who were

children at the turn of the century never knew him, but we always had heard so

much about him that he still seemed to be a neighbor. The house was on Charter

Oak Place, so named because the oak had stood there which had been the hiding

place in 1687 of the Connecticut Charter. Sir Edmund Andros, the royal governor,

had come to take it to England to the King, which he couldn't do.

We sat there

in the library on that long ago afternoon. We each had a book by Joel Chandler

Harris -"Aaron in the Wildwoods" and "Aaron the Runaway."

Aaron was a slave, an Arab, who knew the language of animals. He understood

the mysteries of the swamps-the will-o'-the-wisp and the sound of wind in the

loblolly pine.

Now and then

when I turned a page I looked around the room. Some of the low shelves held

neatly folded newspapers, a complete file of Civil War newspapers. I think it

was The Hartford Times because Mr. Welles had been an editor until Mr.

Lincoln asked him to be a member of his cabinet. He needed someone from New

England.

Once when we

were in the library there was a wooden box in the corner. It was one of the

boxes from the attic, which held all the correspondence concerning the Navy

during the Civil War. There were notes signed A. Lincoln and Seward and Porter

and Farragut. We were interested in Farragut because his flagship had been the

Hartford and her flags were in the State Capitol, but you had the

feeling that Mr. Welles wouldn't want his papers disturbed.

There was a

portrait of him over the white marble mantle in the "best parlor." He

looked like Mr. Lowell, only fiercer. It would be well for children to leave

his papers alone. I wonder now if Mr. Welles' diary was on one of the shelves.

It was called "The Deadly Diary" because it was such a frank

document. Years after his death, when it was published and I read it, I wished

that I might have sat in his library and held the original in my hands. I would

have liked to have read in the stillness of that book-lined room about the gray

day in 1864 when Mr. Welles "witnessed the wasting life of the good and

great man who was expiring before me."

So we sat in

the peace of the late afternoon, lost in stories of other years, shuddering

pleasantly when bloodhounds bayed and "patterollers" rode after

runaway slaves. The little feet of the rain ran more lightly. The wind went away

to ruffle the Connecticut River. The door of the room was open, and from

downstairs came the sound of the piano in the "best parlor" being

played softly, as people often play when twilight glides through the windows in

her gray velvet shoes.

And then into the stillness of the room someone came, someone came

silently as fox fire comes, unseen as wind in the tree tops, but beyond all

shadow of doubting, someone came.

We looked up,

both of us. There was no one we could see. We listened, but we heard nothing,

no mice running in the wall, no creaking board in the floor. Nothing touched

us, no breath of air, no invisible garment. But someone seemed to be there.

I said softly, "Did you think-just now-someone came in?"

"Yes, I did, but I don't see him."

"Do you s'pose it could be your grandfather?"

"It prob'ly is."

"If it is your grandfather, wouldn't it be polite for us to stand

up?" "Yes, it would."

We laid down our books and stood respectfully, as children who lived before the Atomic Age were taught to do when an older person came into a room. You stood because it showed your respect for a person's years, and the wisdom which the years had brought. A disrespectful child came to no good end.

For a short

time we stood there, neither frightened nor amazed. A grandfather is a pleasant

person. My grandfather had been a captain in the Civil War, marched in his blue

uniform in parades, and usually had button peppermints in his pocket. The fact

that we could not see this grandfather did not seem particularly strange. After

all, it was his library.

And then we

heard the heavy steps of Henry Green on the stairs, making a clump-thump sound.

He was coming with a taper to light the lamps. Whoever had been with us went

away. We sat down.

Henry Green

had been a slave in Virginia who had escaped to Washington and attached himself

to the Welles family. He had squeezed whole groves of lemons into lemonade for

very best people - Mrs. Lincoln, a special friend of Mrs. Welles; the Stantons;

the Sewards; Mr. Chase and his daughter, Miss Kate - everybody. He said there

was a cannonball in his back which made him lame.

He came into

the library and said that night and the bats were coming early. He lighted the

lamp on the big round table with the marble top. He drew the plain dark-red

curtains and shut out the darkness. As he left, he turned in the doorway. The

taper made strange shadows on his dark face.

He said, "Ah 'clare to goodness, sometimes it seem lak he was

here." We nodded solemnly. His fingers went into the pocket where he kept

the rabbit's foot. He believed in spirits and witches.

We listened

as he went upstairs to light the lamps in the upper hall. Then he started

downstairs thump-clump. Henry Green had

been the body servant of Colonel Thomas Welles, son of Mr. Secretary Welles.

Once, before a battle, Henry became frightened and fled. But he came to a

bridge on which Mrs. Gideon Welles seemed to appear. She cried, "Go back,

Henry, go back." She was more awesome than the whole Rebel Army, so he

went back. And that was the battle that won the war, so that Mr. President

Lincoln took a gold tack hammer and knocked the chains off the hands and feet

of every slave in America.

Thump-clump.

And after the war Colonel Welles and Henry sailed around the world with Admiral

Farragut. The Devil walked beside the boat and ruffled the water just to be

mean.

We heard

Henry reach the lower hall. We held our books, but we did not read. The

lamplight touched the old books gently. Here and there a book was missing from

a shelf.

At length I said, "Do you think your grandfather was really

here?" "He was here."

"Why did he come, do you s'pose?"

"I s'pose he came down for a book he wanted. Prob'ly one they don't

have in the library in Heaven."

"Do-do-they read Up There?"

"Yes. What else could you do forever and ever, amen?"

And lo, the old New England Heaven of golden

harps, a great White Throne and Cherubim and Seraphim passed away. And the new

Heaven was a vast Celestial Library beyond the foothills of the Pleiades. The

books were bound in solid gold. The reading lamps were of alabaster and the

lights were stars. And those who had been good on earth sat in purple velvet

chairs and read forevermore. But those who had been disrespectful and had not

gone to church on Sunday spent all eternity merely dusting books with dusters

of gray cat-stitched clouds.

And so, when the fingers of the rain are on

the north windows, and the wind cries like a lost lamb, I look back across the

years which make up more than half a century, and see two children standing in

the twilight, standing quietly, respectfully, because they thought Mr. Gideon

Welles had come back to his library.