What's in a Name?

Baby names may reflect Grace; nothing ordinary Will do.

By Karen Goldberg Goff

(Washington Times, 11 May 2003)

Among the most important on the list: What are you going to name the baby? Unlike any of the above decisions, this one sticks with the child for life. Do you go with an old standby such as Katherine or Matthew? Should you look to your cultural heritage? Or go with a trendy name, a unisex name, even a made-up name?

In many cases, it is not an easy choice, says Pamela Redmond Satran, co-author of eight baby name books, including "Beyond Jennifer and Jason, Madison and Montana." Parents have more choices than ever and also are putting more thought than ever into what moniker to place on their child.

"Since the baby boomlet of the 1980s, there has been a whole culture of the fashionable child," Ms. Satran says. "We have the Baby Gap, Pottery Barn for Kids and a lot of fashion-conscious, consumer-conscious parents who are putting a lot of thought into what to name their kids."

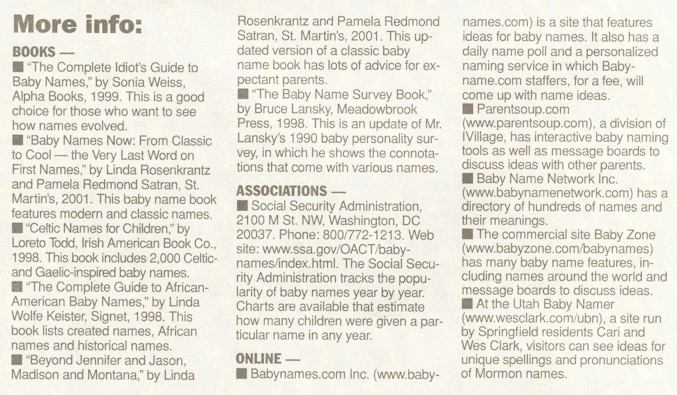

Parents are poring over books and even turning to the Internet, where they might ask total strangers what they think of the combination "Crystal Michelle." Jennifer Moss, a founder of the Web site Babynames.com, says her site has more than 1 million visitors per month. Parents can study the meaning of names and, for a fee, give the Babynames.com staff the task of corning up with a half-dozen ($14.95) or a dozen ($21.95) names.

"They give us criteria, such as if they want a biblical name or a creative name," Ms. Moss says. "About 3,000 people have used our service."

Cindy Belsky didn't turn to experts to help her pick names for her four children, but that does not mean the names came easily to her and her husband, Charlie.

Early in her first pregnancy seven years ago, Mrs. Belsky, who lives in Chantilly, decided if she had a girl, she would name the baby Cadence. The name was unique, had a good flow with their last name and reflected Mrs, Belsky's interest in music and singing, as Cadence means rhythm in music-speak. However, the first Belsky child was a boy, and he stayed nameless for two days until his parents came up with a name, Daniel Frederick. The second child was a girl, so the Belskys got their Cadence, whom everyone calls Cady.

The third child, Evan, was named after a recently deceased friend. The fourth child they named Jared after making lists and lists of names, crossing them out and negotiating with one another. The Belskys are expecting a fifth child this fall.

"I have a book with 30,000 baby names in it," Mrs. Belsky says. "I start flipping through it and write down ones I like or whether they are a possibility. Then I give it to my husband and leave the room. I tell him to cross out what he can't handle, then rank the rest 1, 2, 3, 4. Right now I like Olivia Page if it is a girl. But Charlie and I are still very far apart on names."

YOU'RE GOING TO NAME HIMů THAT?

Names go in and out of fashion, just like nursery wallpaper and Snoopy crib bumpers. For generations, names were basic, usually stemming from the Bible or family traditions, Ms. Satran says.

More recently, names have moved up and down the popularity scale more frequently. Joshua, for instance, was No. 25 in the 1970s but has hovered around No.4 since the 1980s, according to Social Security Administration data. Emily was No. 10 in 1991 but has been No.1 since 1996.

"We have never really been able to identify what makes a name popular," Ms. Satran says. "But it is interesting to see the evolution. The name Mary, for instance, from 1900 to the 1950s was the No.1 or No.2 name. It is religious, straightforward. It was unseated at the top spot by Linda in 1950."

Linda later made way for the Debbies, Marcys and Melissas who are the parents of today's Jordyns, Caitlyns and Calistas.

The 1950s marked the turn in popular culture in America, Ms. Satran says. As television and music took on more significance, people looked to those avenues as sources for names. With the increase in migration out of cities and into the suburbs - even across the country from other family members - people felt more free to pull up the roots of family names as well.

America also became a more multicultural society in the last few decades of the 20th century, Ms. Satran says. The solid English names of the past (William, Anne) melded into Americanized classics (Amy, Steven, Susan) and then a return to ethnic roots (Gabriel, Aidan, Malik, Leah).

Ron and Sonya Kulik, who have four daughters, used a combination of pop culture and just what sounded pretty when picking out names.

Carly, 10, was named after Carly Simon, and the name for Grace, 5, was inspired by the beauty of the late actress Grace Kelly, Mr. Kulik says. The name for Maddie, 7, was inspired by Maddie Hayes, the character on the old TV show "Moonlighting." She could go by the more formal Madeline later in life. Corrine, who is 1, got a name "we just liked, and it sounded good with Kulik."

"Saddling a child with a name is a big thing," says Mr. Kulik, a Reston chiropractor. "But you can get more creative with girl's names. We used names that are not the most popular. The younger three don't have middle names, though, because we didn't want to use a middle name we liked in case we had another child."

In 2003, a few trends stand out, Ms. Satran says:

- Using last names as first names began in the 1980s, Ms. Satran says. Look into any elementary school classroom today, and there will no doubt be a few Parkers, Hunters or Porters.

- Similar to this trend is the use of unisex names, which mirrors the rise of the women's movement, Ms. Moss says. "Names like Jordan, Lindsey and Taylor have leveled the playing field for women when they are out there in the world," she says.

- Place names - such as Cheyenne, Dakota, even a Tennessee or two - are popping up everywhere. And Madison (unisex, last name and the capital of Wisconsin) was the No.2 girls' name in 200l.

- Unique names also stand out. Ms. Satran has a forthcoming book about "cool" baby names. "To be cool these days, it has to be really cool," she says. "Parents want to be individual, and they want meaning. Names that combine those two are going to be very popular in the next 20 years."

Future trends also will include "word names" (such as Destiny, Gardener, Trinity, Autumn) and further popularity of ethnic names, Ms. Satran says.

RULES TO FOLLOW

Want to raise a jock? A nerd? An assertive woman? Pay attention to what name you choose. Names make an impression before a person does, says Albert Mehrabian, a professor emeritus of psychology at UCLA who has studied name connotations for decades.

"Many people do not think about the quality of names," he says. "They think they are being creative or clever, but sometimes they are doing their child an injustice."

Mr. Mehrabian has done several studies asking people to rank names by these characteristics: ethical/caring, popular/fun, successful and masculine/feminine. Names were then ranked by overall attractiveness. High scorers include Alan, Anthony, Benjamin and Elizabeth. Scoring low were Chaz, Butch, Gia and Gertrude.

Similarly, author Bruce Lansky surveyed 75,000 parents for "The Baby Name Survey Book." Among his findings: Nancy, Kathy and Wendy are friendly; Elliott is brainy; David, John and Samuel are intelligent; and Kirby, Kevin, Chuck and Jim are athletic.

Though the choice of names is very personal and individual, there are a few guidelines to keep in mind:

- Think about the future. Do you want Kelleigh to have to spell her name or correct her teacher every time it is mispronounced? Also, Mistee might be cute for a toddler, but will the jury take her seriously should she become a lawyer someday? "People are not thinking about 25 years from now," Mr. Mehrabian says.

- Check out who else has the same name. Look in books and online to see what the most popular names of the last couple years are, Ms. Moss says. For instance, you might love the name Ashley, but because it's No.4 on the 2001 list, there very well may four Ashleys in the classroom in a few years. Fairfax couple Julia and Greg Malakoff named their first son Benjamin when he was born four years ago. They liked that it was a traditional name, that they were honoring the Jewish custom of naming him after a relative and that they didn't know anyone else with that name. Turns out Benjamin was a hot name in 1999. There are three Benjamins in their son's age group at preschool. "Of course, none of them are shortened to 'Ben: so they are all called Benjamin, along with their last names," Mrs. Malakoff says. "The kids in the class think his first name is Benjaminmalakoff."

- Think about what is important to you. Are you honoring a family member or friend? There are ways to do that and still give the baby an individual identity, Ms. Moss says. You can use a family name as a middle name, for instance.

- Spell it, say it, write it and write the initials. A name that is too long is going to be tough for young children to say. The general rule is that long last names go better with short first names, and vice versa. Checking what the initials will spell will ensure you don't give the child initials such as "UG.H." or "H.A.G," Ms. Moss says. Also, in dealing with multicultural families, investigate the meaning of the name in several languages. A name that says "beloved" in one tongue may say "angry" in another, for instance.

- Learn to compromise with the extended family. Just as everyone will give advice on how to get baby to sleep through the night, relatives will chime in on what to name, or not name, the baby. You can break tradition if you want to, and many siblings have fought over names for which they previously called dibs. Ms. Moss says there is a way to work it out. "It is not worth it to fight over a name," she says. "There are so many names out there."

- Finally, feel free to change your mind once you get a look at your baby's face. "I am a strong believer in not naming a child before he is born," Mrs. Belsky says. "Jared was going to be named Nathan Austin. But he was born and just did not look like a Nathan."

Names reflect cultural origins

By Karen Goldberg Goff

Many cultures have traditions that are unique, ancient, even mystical ways of bestowing names upon children.

That includes making up names. In America, two cultures in particular - the black and Mormon communities - are well-known for inventing names, says Pamela Redmond Satran, author of eight books on baby naming. Both cultures began the practice to create their own identities, Ms. Satran says.

"When slaves were first brought here, slave owners typically gave blacks biblical names that were not used by whites," she says. "Then the tradition moved into being known by the slave owners as one thing and by the family as another."

After the Civil War, naming records began to include women's names with -inda (such as Clara becoming Clarinda) as blacks began to forge an identity that was separate and unique. That segued into the practice of suffixes such as -on, -won, -quon and -el for boys (Juwon and Ronel, for example), and prefixes such as Shan-, Ka-, and La- and suffixes such as -isha and -el for girls. Examples: LaKeisha, Monisha, Danell.

"African Americans were the first in this country to start inventing names," Ms. Satran says. "In a way, whites have imitated that as they tried to find out-of-the-ordinary names."

Mormons also have given children invented names - or at least names with inventive spellings - for years, says Cari Clark, a Springfield woman who founded a Web site devoted to creative Utah baby names.

"Many times people will blend two names together to use some really wild spellings or the prefixes La- or Da-," says Mrs. Clark, who lists thousands of names on her site. "A lot of families are large, so they want each child to have a unique name. Also, many families in Utah have common names such as Clark, Smith or Young, so they try for an extraordinary given name to offset the ordinariness."

Some of the names listed by Mrs. Clark: Alinda, AndiOdette, Breawn, DeVaughn, Dwendle and Claron.

"I once had a friend named M'Lou," she says, "and I know of a Cliphane (rhymes with Tiffany)."

Other distinctive cultural practices:

- Jews with roots in Eastern Europe commonly name their child after a deceased relative. The custom is based on a superstition from the Middle Ages that the Angel of Death may mistakenly take the child away if his namesake should die. Sephardic Jews (those hailing from the Mediterranean) name their child after a living relative in order to give the youngster a role model.

- Catholic tradition is to name a child after a saint. That can be found in the United States, but also in many countries, such as Italy and throughout Latin America, where there are large numbers of Catholics.

- Many Muslim children are named after the prophet Mohammed or members of his immediate family, This is why the name Mohammed, along with its variants, is one of the most popular names in the world, says Sonia Weiss, author or "The Complete Idiot's Guide to Baby Names."

In many Eastern cultures, such as in China and India, families choose names that have great symbolical meaning. Pam Jah, a Reston woman who is originally from India, chose the names Rohit ("red") and Ankit ("conquered") for her sons. "I wanted to give them traditional Indian names;' says Mrs. Jab, whose given Indian name is Padmja ("lotus"). "A lot of times, children will be given two names, one for at school and another for at home."